All roads lead to removal: replacing two statues and redefining campus space at Brown

By Amanda Brynn, Justin Han, Sam Kimball, Junaid Malik, Olivia Mayeda, and Kelley Tackett

Last spring, Brown’s Public Art Committee proposed to restore and relocate the bronze copy of a Roman statue of Augustus, which currently stands in front of the Ratty, using tens of thousands of dollars solicited from an unnamed donor. Under this proposal, the statue would be moved to the Quiet Green, across from the Slavery Memorial.

We strongly oppose this proposal and urge the Public Art Committee—and any community members or donors who are invested in the role of public art at Brown—to replace both the statue of Augustus and the statue of Marcus Aurelius (currently on Ruth Simmons Quad) with new works of art commissioned from local Black and Indigenous artists.

These monuments were brought to our campus with the goal of upholding the ideals of the “perfect” white form, white civilization, white supremacy, and colonialism—ideas that we believe are incompatible with Brown today. Consequently, removing and replacing these statues is a crucial step in confronting such legacies. We see this as a moment of immense opportunity for transformation and reflection, and we hope that the broader campus community, the Public Art Committee, and potential donors will, too.

More than a Gesture

We recognize that the removal of these statues alone does not constitute decolonization at Brown. Instead, this is one step in a broader project of decolonization by confronting Brown’s institutional and ideological legacies of colonialism and white supremacy. Our focus on monuments is a recognition that these kinds of statues physically and metaphorically occupy our imaginations and understandings of what has passed and what is possible.

Beyond the gesture of removal, we are also committed to advocating for broader structural changes. Over the past several months, we have already successfully advocated for an expansion of the Public Art Committee to include more perspectives from faculty and students. Moving forward, we aim to change the way art is commissioned at Brown, particularly with a focus on art by Black and Indigenous artists. Currently, of the 30 pieces of public art on campus, only three were created by artists of color, only one of whom is Black, and none Indigenous. We hope that instead of spending tens of thousands of dollars towards the maintenance, restoration, and relocation of the Marcus Aurelius and Caesar Augustus statues, this money will instead be invested into works produced by local Indigenous and Black artists. This further material movement of wealth back into the broader Providence and Rhode Island communities would form an important part of ongoing structural change at Brown.

The Origin of the Monuments to Marcus Aurelius & Augustus Caesar

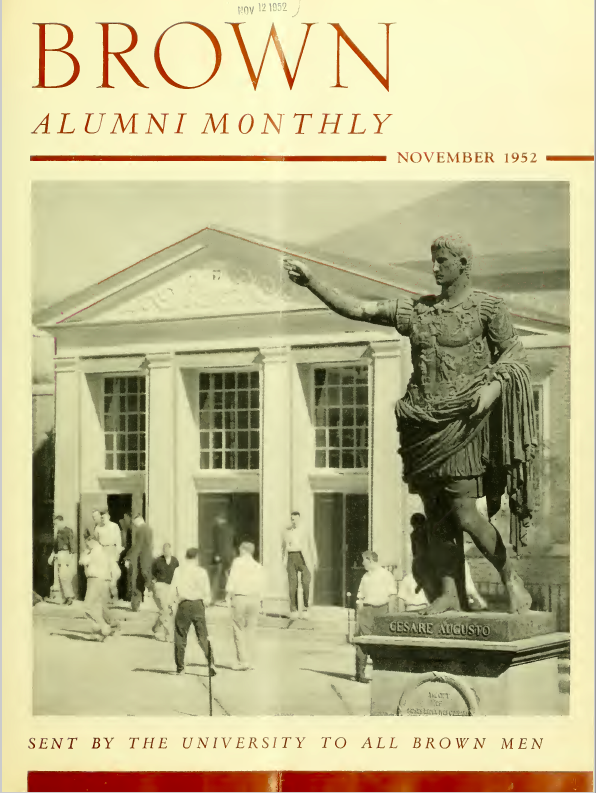

The statue of Caesar Augustus was donated to Brown in 1906 by Moses Brown Ives Goddard, where it occupied the space in front of Rhode Island Hall on the Quiet Green. It was moved to its current location on Wriston Quad in 1952. Similarly, the statue of Marcus Aurelius was given to Brown in 1908 by Robert Hale Ives Goddard, welcomed in a ceremony with intense fanfare. These two statues of Roman emperors are not actually Roman statues – they were made in 1906 and 1908 as bronze casts (copies) of existing statues from antiquity.

Because they are not actually from ancient Rome, we must understand them as modern monuments to a set of values and political stances which existed when they were commissioned for Brown’s campus.

The 1906 Brown Alumni Monthly described the Caesar Augustus statue as “featur[ing] a truly regal gaze which seemed almost to be directed back through the centuries ... indeed an emperor of the Roman people at the zenith of their glory.” This directly locates Brown University’s ancestry in Imperial Rome. William Carey Poland, then Professor of Art History, wrote in the July 1908 issue of the Brown Alumni Monthly of the Marcus Aurelius statue that “we are not without an interest in all that this monument that it has signified to men of culture who have appreciated it," that "we express our undying gratitude to him.”

These descriptions of the statues’ arrival leave no room for misinterpretation: the education for students at Brown—which, then, was almost exclusively white elite men—was designed to mold them according to the classical ideal of whiteness. This ideal is the origin of the monuments, not an interpretation or argument against them.

The Brown Alumni Monthly, December 1906 (volume 7, no 5) published this racist “anecdote” about the statue of Caesar Augustus, which demonstrates the imagined lineage between the predominantly white men at Brown and this ancient Roman figure. They used the statue to distinguish between those who were inheritors of this lineage and non-white people who were seen uneducated, uncivilized, and uncultured.

How are these Statues harmful?

The connection between the U.S. and Rome is entirely ideological. There is no natural or direct tie between the two—there is only a fabricated lineage of whiteness. Statues made in the Roman-style, like the two at Brown, are intended to materialize this connection. They convey the supposed supremacy of white values over non-white cultures, a reading in which non-white people should learn and aspire to whiteness. Alt-right groups, like the Proud Boys and Identity Evropa, use this idea of “white virtue” to ground white supremacy.

The broader mythology of white civilization, emphasizing Roman connections to the U.S., has also been central to legitimizing the American settler-colonial project as well as subsequent U.S. imperial interventions across the world. The systematic killing, forced assimilation, and displacement of Native peoples in North America was and is justified by “racial logics and romanticized histories." Foremost among these is the notion that the U.S. “is the culmination of Western civilization, the product of a genealogy...from ancient Greece and Rome to Christian Europe.” These same ideas underpin the statues at Brown. In Poland’s aforementioned comments in the Alumni Monthly, he exclaims: “we stand here, thrilled by the revelation of this imperial figure of the monarch, the great conqueror, the law-giver, the philosopher.” To claim this history is to claim the same ideas that justified the occupation of indigenous land in the U.S.

It is no coincidence that Roman-style statues venerating conquest and domination continue to occupy land in other European colonies, including Algeria and India. Within this broader context, Roman-style statues function to monumentalize the celebration of European rule over non-white peoples in the Americas, Africa, and elsewhere. Given the profound ongoing violences of colonization, including physical and cultural genocide, systemic dispossession, and the continued occupation of Indigenous lands in Rhode Island and the U.S., this oppression should not be celebrated, let alone monumentalized.

Image from June 1, 1908, the unveiling ceremony for the Marcus Aurelius statue.

Sourced from the Brown Alumni Monthly.

Racist Canons and Aesthetics

These Roman-style statues are also direct products of white supremacist idealization of white features.During the 1906 unveiling ceremony of the Caesar Augustus statue, recorded in the Brown Alumni Monthly (vol 7, no 3), President William Faunce described it as “the finest specimens of manhood and physical development of any age.” The presence of these kinds of statues is also a declaration of the ideal person, a white elite man who fits these racist physical standards. To the significant number of students, staff, and faculty at Brown today who are not white, these statues function as a constant reminder that Black, Indigenous, and people of color are not included within Brown’s conception of the University community. The presence of these statues is therefore not only incompatible with, but violates Brown’s stated commitment to inclusion, equity, and change.

It is important to note that this is not just about monuments. It is also about the kinds of people and histories that students at Brown today are taught to idealize. Disciplines at Brown continue to be dominated largely by “classical” canons, comprised of scholars and scholarship that is almost entirely Western and white. The replacement of these statues not only removes images that honor Brown’s history of violence, institutional racism, and settler colonialism, but also forces us to confront the legacies of imperialism and colonization that continue to shape our education. Removing images that honor this history is not analogous to removing the history itself. We will continue to recognize and reckon with Brown’s legacy as an institution – implicated in white supremacy and colonialism – while and after these harmful monuments are removed.

Contextualization is not enough. Moving it only relocates harm.

It is not enough to attach a plaque or add new sculptures in an attempt to contextualize these statues. The long, violent, and ongoing histories of white supremacy and settler colonialism monumentalized by the Caesar Augustus and Marcus Aurelius statues will always overshadow any intervention. Creative or critical interventions do not resolve the harm that these statues perpetuate through their physical presence. Moving the statues does not remove these associations, as Brown’s 1952 Alumni Magazine (vol 53 no 2, inside cover) itself noted during the relocation of the Caesar Augustus statue from the Quiet Green to the newly constructed Wriston Quad. The magazine described the statue as “a natural ornament for [Wriston], tying the new area to the older traditions with this landmark." By choosing to stand by “older traditions” of white virtue and classical education manifest in the statue of Caesar Augustus, Brown materially affirms these embedded ideologies. In effect, relocating the statues would do nothing more than to relocate harm.

Beyond the harm of the statue itself, the proposal seeks to place the Caesar Augustus statue in relation to the Slavery Memorial. This would directly undermine the purpose of the Slavery Memorial. One work remembers Brown’s past and present relationships to racial slavery in the U.S., perpetuated through colonialism; the other glorifies a symbol of white supremacy and white civilization.

Ultimately, this relocation would compromise the intent of the Slavery Memorial, allowing a symbol of white domination to tower over a memorial to the suffering dealt by white supremacy.

Reimagining the Future

This is not simply a metaphorical step towards decolonization. We are concerned both with the present and future of public art, monuments, and statues at Brown. Removal creates avenues for replacement and reallocation, by which Brown can choose to redefine its relationship to—and in collaboration with—local Black and Indigenous communities through investment in local artists and arts organizations.

At the time of publication, our task force has successfully advocated for the expansion of the Public Art Committee following nearly a year of research, advocacy, and collaboration with administration, faculty, and dozens of student organizations. This includes the addition of two undergraduate student positions, as well as two new faculty members. Decisions concerning public art have historically excluded non-white students, staff, and faculty. Our hope in expanding the Committee is to widen the scope of ongoing conversations concerning public art on campus, to think about public spaces not just through an artistic lens, but also to consider the ways histories, narratives, and ideologies—particularly colonialism and white supremacy—produce and maintain particular understandings of the university.

Our student organization, Decolonization at Brown (DAB), works broadly toward the reimagination and decolonization of university academics, spaces, and relationships. In addition to advocacy relating to public art on campus, some of DAB’s work includes collaborating with students, faculty, staff, local communities, and administrators to systematically integrate non-Western paradigms within syllabi and curricula; the hiring and retention of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) faculty; building serious, reciprocal relationships to local and Indigenous communities in the Providence and Rhode Island communities; and more. DAB also stands and works in solidarity with the efforts of other organizations toward the abolition of policing on and off campus, achieving housing justice in Providence, enacting corrective measures in response to Brown’s historic and ongoing displacement of Fox Point and Mt. Hope residents, and ensuring Brown continues its obligation to make reparative investments in Providence K-12 education.

Finally, Decolonization at Brown would like to express our immense gratitude to the many student organizations who have so far offered their explicit endorsements of our call to remove and replace the statues of Augustus and Marcus Aurelius. At the time of publication, these student groups include:

African Students’ Association (AfriSA)

Archaeology DUG

Assyriology & Egyptology DUG

Bengali Students’ Club (BSC)

Black Student Union (BSU)

Brown Asian Sisters Empowered (BASE)

Brown Birding Club

Brown Muslim Students’ Association (BMSA)

Brown Organization of Multiracial and Biracial Students (BOMBS)

Center for Language Studies

Education DUG

Environmental Justice at Brown (EJ)

Environmental Studies/Science DUG

Hawai’i at Brown (HAB)

Independent Concentration DUG

Iranian Students’ Association

Kashmir Solidarity Movement (KSM)

Literary Arts DUG

Mixed Asian Pacific Islander Students’ Heritage Club (MASH)

Natives at Brown (NAB)

Pakistani Students’ Association at Brown (PSAB)

Philosophy DUG

Portuguese and Brazilian Studies DUG

Slavic Studies DUG

Southeast Asian Studies Initiative (SEASI)

Storytellers at Brown

Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP)

Students Organize for Syria

If you would like to endorse this project, either as an individual or on behalf of an organization on campus, an endorsement form is available here.

Images via Brown Alumni Monthly, November 1952, and sources listed in captions.