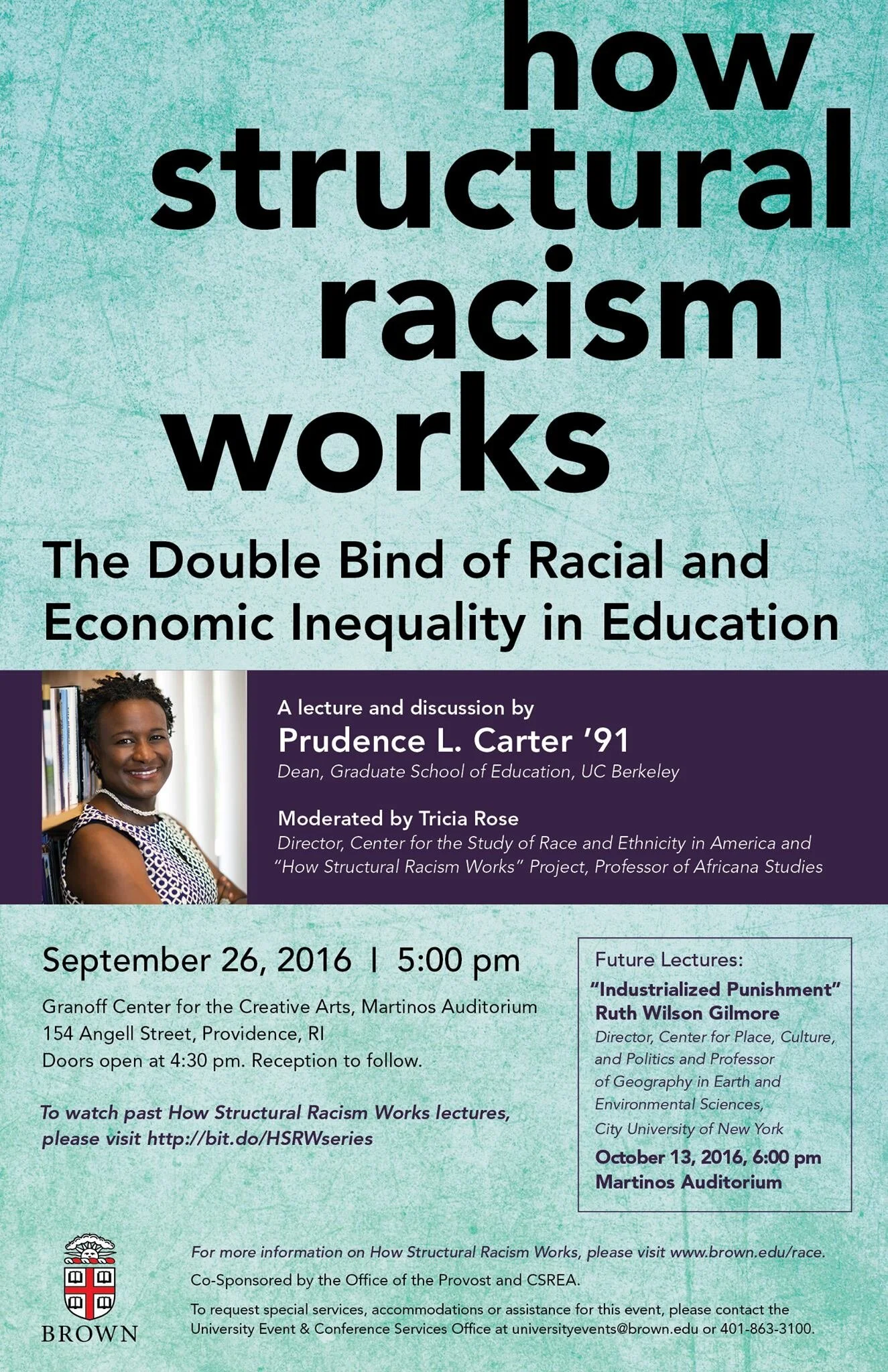

How Structural Racism Works: Education

On Monday night, a full house gathered in the Martinos Auditorium to hear Dr. Prudence L. Carter '91, Dean of the Graduate School of Education at UC Berkeley, give a lecture entitled, "How Structural Racism Works: The Double Bind of Racial and Economic Inequality in Education."It was the sixth lecture in a series called "How Structural Racism Works," a project that is the brainchild of Professor Tricia Rose of the Africana Studies department.Dr. Carter grew up attending Mississippi public schools, received a Bachelor of Science degree in APMA from Brown, and then got both her Master's and PhD degrees from Columbia.Right away, Dr. Carter showed the audience this article from the NY Times. I highly recommend you look at it. It shows the faces of the 503 most powerful people in this country. Included were government officials, CEOs, presidents of Ivy League Universities, influential publishers, and more. Only 44 of those faces belong to people of color.As Dr. Carter explained, these are the faces of the gatekeepers of every sociopolitical, cultural, and economic aspect of American society. The overwhelmingly white list "is not a normal distribution of talent." The fact that so many white faces appeared on that screen clearly undermines the notion that people who deserve positions of power the most will receive them.So, after demonstrating the effects of structural racism, Dr. Carter moved back into the realm of our current education system. How does our education system contribute to the perpetuation of a 91% white ruling class (I'm doing it-- I'm callin' those 503 people the ruling class. They really are important and prominent and therefore ruling people).Well, first we have to look at the racist history and laws of this country. One example of a racist law that perpetuated educational inequalities is the GI Bill of 1944. This bill, for all intents and purposes, only applied to white veterans. It demarcated "nice, suburban" (read: white) neighborhoods for returning veterans. Similarly, all educational funding went to white veterans. And the reverberations of this act can still be felt now. I'm from Massachusetts and I can assure you all of the overwhelmingly white suburbs in my state have the best public schools.Dr. Carter explained that we maintain these neighborhood boundaries through "othering" people. She has heard people say many times that the racial homogeneity in their neighborhoods isn't a representation of racism or segregation, but that they just like to spend time with people "like them." She quipped, "Why, of course, you are more likely to spend time with other people 'like you' if you are segregated!" Referring to the fact that white students in diverse schools generally hang out with other white kids and that students of color generally hang out with other students of color, she added, "Even when we go to school together, we divide ourselves because we do it at home; we do it in our neighborhoods. We are the vehicles that carry the baggage of segregation."Lastly, she explained that the way we conceptualize education in this country is inherently flawed and promotes structural racism. Thinking of education in terms of "social mobility," or more specifically, thinking of education as a way to get ahead of the next guy in the competition for resources and wealth is particularly detrimental because "we 'other' the people we are competing against." And, in a majority white country, those 'othered' people are people of color. Our education's system's insistence on "equal treatment" also promotes inequity. She used a well-known cartoon to show the difference between equality and equity. We need a more equitable education system that is less focused on giving each student "equal" resources without taking their inherent privileges or disadvantages into account. She presented her ideas for solutions in three categories:"Macro" level solutions included better job policies, a stronger democracy, better housing, and ultimately, recalibrating the ridiculous wealth disparity in this country."Meso" level solutions included diminishing the pervasive treatment of education as a private good and building more supportive local communities."Micro" (or individual) level solutions included erasing prejudice, eradicating bias, the full incorporation of diverse identities, and the viewing of education as a public and private good.During the Q&A portion, a man asked, "Where do you see hope [for improvement] in this world?"And Dr. Carter replied, "I always have hope in the next generation. [...] Vote." And in our current political climate, her words carry more weight than ever.Keep an eye out for an announcement of the next lecture in this series and definitely try to attend.Image via and via.

She presented her ideas for solutions in three categories:"Macro" level solutions included better job policies, a stronger democracy, better housing, and ultimately, recalibrating the ridiculous wealth disparity in this country."Meso" level solutions included diminishing the pervasive treatment of education as a private good and building more supportive local communities."Micro" (or individual) level solutions included erasing prejudice, eradicating bias, the full incorporation of diverse identities, and the viewing of education as a public and private good.During the Q&A portion, a man asked, "Where do you see hope [for improvement] in this world?"And Dr. Carter replied, "I always have hope in the next generation. [...] Vote." And in our current political climate, her words carry more weight than ever.Keep an eye out for an announcement of the next lecture in this series and definitely try to attend.Image via and via.