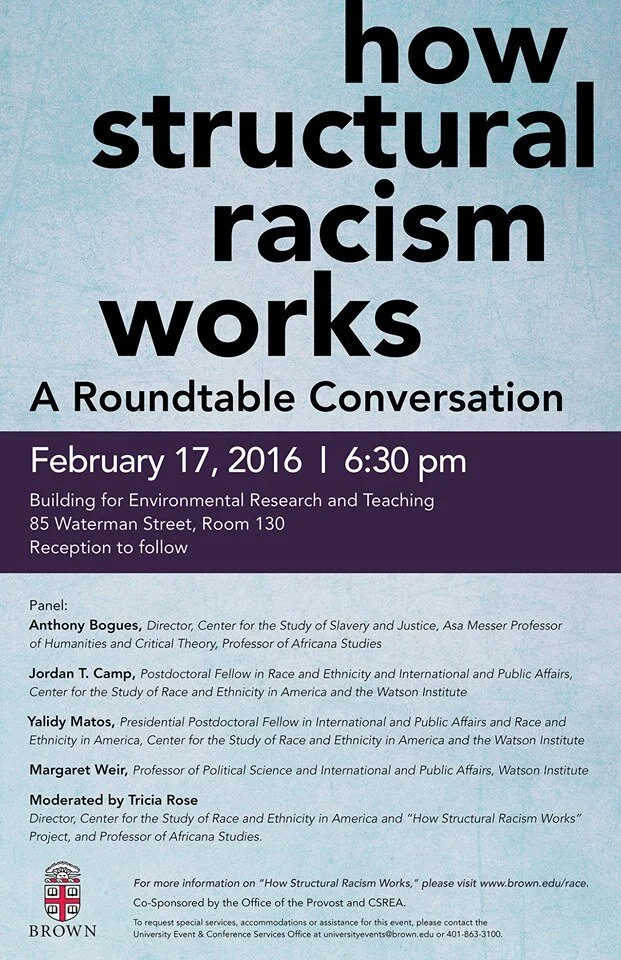

How Structural Racism Works: A Roundtable Conversation

Provost Richard Locke welcomed a full house at Wednesday night’s panel, How Structural Racism Works: A Roundtable Discussion. The panel was moderated by Africana Studies Professor and Director of Brown’s Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America (CSREA) Tricia Rose as the second installment of a larger video, workshop, and public engagement lecture series.The panel members were Anthony Bogues, Director at the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice; Jordan Camp and Yalidy Matos, Postdoctoral Fellows in Race & Ethnicity and International & Public Affairs at the CSREA and the Watson Institute (Matos is also a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow); and Margaret Weir, a Political Science and International & Public Affairs professor at the Watson Institute. Locke framed the evening’s conversation by acknowledging that “as a university, there are things we can and must do” to combat issues like structural racism (defined by Rose as “the normalized and legitimized range of policies, practices, and attitudes that routinely produce cumulative and chronic adverse outcomes for people of color”). He spoke of combatting the issue “through the faculty we hire, the curriculum we teach…the leaders we cultivate, and the policies we can affect.” He noted that, as provost, his goals are to advance academic excellence in ways that strengthen the community—goals that inherently necessitate fostering diversity and inclusivity. Locke sent a school-wide email five days prior to the lecture, encouraging the Brown community to attend the events of the lecture series.The panel had three recurring themes, and each panelist spoke extensively about their areas of expertise. As the panel progressed, they conversed and answered audience questions.The Prison-Industrial Complex (PIC)The Prison-Industrial Complex is a term used to describe the imprisonment, policing, and surveillance of non-white (specifically, black male) bodies to “combat” economic, social, and political problems. Camp spoke of the history of Jim Crow laws, noting that with their outlawing, the PIC became more and more prominent. He highlighted the 1960s and the time immediately after World War II as key moments in history for structural racism, during which Black people were disproportionately under- or un-employed at a rate comparable to that of the Great Depression. Black protests against these economic conditions “phased and translated into narratives of law and order, and security.” These narratives were then used to “justify” the construction of the PIC. Instead of granting access to education, healthcare, or social programs, the funds from these projects were then redirected into the expansion of policing practices and securing urban spaces.Space and PlaceWeir spoke about spacial inequality, an important theme in discussions of structural racism in urban environments. She mentioned that while there exists significant literature on the history of Black-White separation, there is a surprising lack in studies of how people are divided by boundaries or how those boundaries come about. She spoke of the ways in which cities like Atlanta, Detroit, and Flint exemplify problems that specifically non-white communities face such as transit racism (defined as the disproportionate way in which low-income POC have little access to transportation from their neighborhoods to the high-income locations where they work) and inequality of opportunity. Matos spoke specifically of immigration, expanding on Weir’s point of boundaries and borders as “enduring things." She spoke of the “history of the border” which criminalized Mexican people and displaced them in their own country (referring to the once-Mexican territory acquired by the U.S. in 1848). Matos spoke further of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations as institutions that literally police space, and spoke about how ICE specifically targets non-white people and treats them accordingly. It is important to note, Matos said, that during the Bush administration, ICE moved from the Department of Justice to the Department of Homeland Security, thus highlighting the rhetorical and ideological shift from immigration as a justice matter to a matter of national security. This is materialized through the “regulation of the border” and the question of “who gets to cross it”. Thus, Matos said, space—specifically urban space—becomes racialized, (i.e. Harlem is an example of a “Black, therefore criminal” population.) Moreover, she noted that the term “urban” is a contemporary coded and racialized word for Black and low-income. The panelists noted that these histories and the policing of spaces are seen as “normal.”NormalizationWeir identified normalization as a pillar of structural racism that is “written into American local law.” Bogues defined normalization as “a construction of a common sense which is about racial bodies.” In other words, as stated by Weir, communities believe that their conditions are just “the way it is.” Bogues argued that racialized bodies are treated in a certain way, in terms of specific discourses and rules that place and classify the bodies specifically. These are “lacking” and always result either in treatment of the bodies as “needing to be controlled" by criminalization or incarceration or in treatment of the bodies as exceptions (such as ICE's treatment of Mexican immigrants). Bogues then posed a question for the room, asking at what moment we began to understand difference via racism. Members of the audience clapped and snapped, indicative of the lecture's core. The audience was diverse, comprised of students of all sorts of genders and ethnic identities; of undergraduate and graduate students; and of professors, faculty, and members of the Providence and broader Rhode Island community.This lecture series will continue throughout the semester. Provost Locke’s recent campus-wide e-mail contains information on the other events, including one on Friday, March 4 at noon in the Cogut Center and others on March 24 and 25. The e-mail also provided students with a link to the series’ website, where they can find information about each lecture.Image via.